What have we learned over a decade on since the global land rush?

Authors: Christoph Kubitza and Danya-Zee Pedra

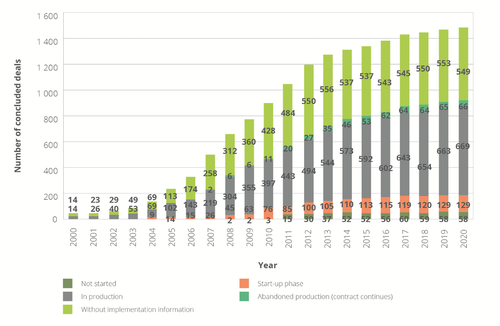

Current spikes in global food prices bring up old memories of similarly escalating food prices in 2007/2008 and the associated rush for agricultural land in developing countries. Seeing these recurring patterns in prices, it is ever more urgent to understand if the past global land rush was sustainable at any level in the first place. A recent report by the Land Matrix Initiative, Taking stock of the global land rush: Few development benefits, many human and environmental risks, launched in a webinar in the last week of September, provides evidence to the contrary. The results from the report and the webinar show that more than 10 years after the surge of large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) by international investors for agricultural production, the impacts in developing countries are sobering, in part alarming – although perhaps not surprising, given that a substantial 1 865 deals have already been registered in the Land Matrix database since the year 2000, with a staggering total targeted size of 33 million hectares (comparable in size to Italy or the Philippines).

Cumulative number of concluded land deals globally

Note: Calculations based on Land Matrix data. Although there are 1 099 concluded deals currently in operation, the number of operating deals in this dynamic illustration only adds up to 669 due to missing implementation year information, indicating that this should be interpreted as a lower bound. Likewise, the number of abandoned deals is under-reported in the dynamic illustration, but the accumulative number of projects not yet started and in start-up phase are almost exactly reflected in the dynamic statistics.

Source: Taking stock of the global land rush: Few development benefits, many human and environmental risks. Analytical Report III.

While these investments often originate from high-income countries such as the USA and the Netherlands, investors from middle-income countries such as China and Malaysia are also heavily involved in this global business. Irrespective of where the investors are based, these deals often have dire consequences for local communities in the target countries. Too often they lose access to their ancestral lands and at the same time reap only little socio-economic benefits from the investments – be they employment, newly introduced technologies, or infrastructure. “Employment creation in particular is where we see the expectations of local populations far exceed the number of jobs that most large-scale projects are or are planning to generate,” explained Jann Lay, one of the authors of the report, during the launch of the report, adding that they “contribute little to the problem of rural underemployment, and may even aggravate it.”

These LSLAs fall short of their initial expectations when it comes to national economic development and food security as well. For example, overall, less than 0.5% of the national workforce will be employed on the acquired land in the majority of countries since labour intensity is often low due to mechanised farming. These land investments are no remedy for precarious labour markets either, as temporary and underpaid jobs prevail. Likewise, national food security rarely benefits from LSLAs, since most investors focus on international commodity markets, as seen with the oil palm-related deals captured in the Land Matrix database, which account for more than 20% of the area currently cultivated with this crop worldwide. Other cash crops, such as rubber, sugar beet, and sugar cane, are also among the most important commodities. This focus on cash crops casts doubt on the expectation that LSLAs will substantially improve local food security and help to forestall the global increase in undernutrition that was reported in a recent report on the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021.

Besides these socio-economic concerns, there is overwhelming evidence that LSLAs are a major threat to forests and other natural resources. For instance, 39% of agricultural LSLAs fall at least partially within biodiversity hotspot areas. In the past 15 years, global land investments have also opened new deforestation frontiers worldwide, with the highest loss of forest cover found in Southeast Asia, where, according to the Land Matrix estimates, about 1.3 million hectares were lost between 2000 and 2019 within the contract area of LSLAs that were registered in its database – and the loss of forest is likely far from over given that, as the authors highlighted during the report launch that implementation rates are still relatively low, but as they pick up speed more deforestation can be expected to take place, in Asia and beyond. But more than just forests are under threat – 54% of the land deals recorded in the Land Matrix database are intended to produce crops with high water use, which drastically increases pressure on local water resources and is thus an important dimension of the environmental consequences of uncontrolled land acquisitions.

Ultimately, the report clearly shows the urgent need to transform current practices of LSLAs into responsible and sustainable contributions to economic and social development. Yet, although progress has been made in terms of land governance, a lack of implementation and compliance with policies is evident. This is particularly apparent from an assessment of the application of the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure (VGGTs). “In Africa, for example, almost one-third of the deals assessed do not comply with the VGGT guidelines and standards at all,” pointed out Ward Anseeuw, another of the report authors. One way forward to ensure better compliance and implementation is to “build capacities of professionals working in government ministries that deal with land and investment to be able to negotiate better contractual terms and agreements when land is being allocated,” Janet Edeme from the African Union Commission commented, adding that “we need to ensure that in-depth scrutiny and due diligence of potential investors is undertaken.”

However, more than just compliance with policies and guidelines need to be ensured, emphasised speaker David Kaimowitz from the Forest and Farm Facility. “Strengthening local rural organisation – of small farmers, pastoralists, forest communities, indigenous peoples – is essential to address this issue,” he stressed. “If the inhabitants on the ground do not have strong organisations and a capacity to consolidate their own economic activities and advocate effectively for their rights, it will be practically impossible to limit inappropriate large scale land acquisitions.”

While the development community has different views on desirable or feasible patterns of rural development and which instruments, policies, and priorities are required to achieve this in a sustainable way – there is overwhelming consensus that, by and large, LSLAs have not delivered on their promises for rural development and that much remains to be done to improve the status quo.

LSLAs threaten local communities’ access to land

Photo credit: Markus Giger (2012)

About the Land Matrix Initiative

The Land Matrix Initiative (LMI) is a partnership between the Centre for Development and Environment (CDE) at the University of Bern, Centre de cooperation Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD), German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and International Land Coalition (ILC) at global level, and the Asian Farmers’ Association for Sustainable Rural Development (AFA), Centre for Environmental Initiatives Ecoaction, Fundación para el Desarrollo en Justicia y Paz (FUNDAPAZ), and University of Pretoria at regional level. Established in 2009 to address the gap in robust data on the real extent and nature of the “global land rush”, the LMI has evolved into an independent land monitoring initiative that promotes transparency and accountability in decisions over large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) in low- and middle-income countries in response to the need to monitor such complex investment flows.